作者:wing.cheng

1. Introduction: Contestation of Narratives

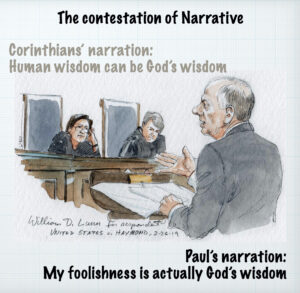

Focusing on 1 Corinthians 4:9, this essay is guided by a main research question: “why are the angels included among the watchers of the spectacles wherein God has exhibited the apostles the last, as those condemned to death?” It is proposed that a contestation of narratives is reflected in this verse. To argue against the narrative of the Corinthians, from which their ecclesicial problems arise, Paul nests the story of the Corinthians to the apocalyptic story of the fallen angels by the thematic resonance of wisdom. Meanwhile, his own story is nested to that of Christ by the theme of foolishness. Thereby, he intends to argue for his own apostolic identity as well as his teaching, rebuking and rectifying Corinthians’ problems.

In 4:9-10, Paul was staging a contestation of narratives wherein he intended to rebuke Corinthians’ narration concerning foolishness and wisdom and established his narration. Why is narration involved? A particular narration stems from one’s particular emplotment of an event. The same event can give rise to multiple narrations since every emplotted narrative is not an exact replica of the event, but a self-involved and ethically engaged organisation.[1] In the case of the Corinthian community, regarding what wisdom and foolishness are, Paul and the community held respective narrations that are in contestation. In Chs.1-4, Paul has already set forth a thematic dichotomy between wisdom and foolishness.[2] Taylor also points out that 4:6-13 is the climax of Paul’s dichotomous argument.[3] Therefore, the contestation between wisdom and foolishness acts as the larger context from which we should understand 4:9-10, which aligns with Paul’s rhetorical purpose: arguing against human wisdom with “foolishness” of the cross. Hence, the question follows is how Paul argues with 4:9-10 to achieve his rhetorical purpose. The answer, which is comprised of the methodology of a nesting of stories and the metaphor of theatre, is to be explicated. Beforehand, the narratives of Corinthians will first be introduced by analyzing their problems.

2. Paul’s Counter-argument Against Wisdom

Corinthians’ Narrative

Paul’s epistles are contextual writings that address ecclesial problems.[4] Hence, identifying the problems will shed light onto Paul’s rhetorical purpose and strategy. In short, the Corinthian culture is marked by a kind of self-centeredness that its inhabitants strive for self-gratification in terms of reputation, sex, economical or social status. Thus, the culture inevitably bears facets of self-promotion and competitiveness, which are associated with autonomy, self-sufficiency.[5] Also, Corinth was known for its notoriously wickedness, filled with vices of idolatry, sexual immorality and associated sins.[6]

As Anthony Thiselton observes, “Christians” in Corinth carried over into the church these cultural traits,[7] and their own social status,[8] and thereby developed an over-realized eschatology coupled with success-oriented triumphalism,[9] which makes them perceive their current abundance in wisdom or material coming from the milieu as spiritual blessings[10] instead of worldly temptation. In terms of Ricoeur, their “criteriology of the divine”[11] is success[12] and wisdom, against which they judge and discern whether a teaching fits their understanding of God.[13] It means that a certain teaching has to be compatible with their success and wisdom so as to be counted as divine, otherwise, it is rejected. Such a theology constituted different ecclesial problems,[14] of which concerns us chiefly is that they questioned the apostle’s leadership as well as challenged his prior instruction.[15] They demanded freedom in choosing their own leaders,[16] thus causing division[17] and rivalry among the communities. Second to this is that they formulated their own ethics[18] to rationalize their immoralities. All these stem from their self-perception laden with overly-realized eschatology, seeing themselves as those who reign (1 Cor 4:8) with sufficient wisdom and capacity.[19]

If the analysis above correctly pins down wisdom and success as two of the vital parameters of their criteriology of the divine, Paul was causing pain to argue against this criteriology by substituting their wisdom with “foolishness” of the cross.[20] The methodology behind this rhetorical strategy he employed can be articulated by nesting of stories.[21]

Nesting of Stories in the Contestation of Narratives

Within Paul’s counter-argument, I argue that Paul nested the story of the angels on that of the Corinthians to boost his rhetorical effectiveness. According to a generally accepted understanding of narrative, every story/narrative can be seen as consisting of three temporal units: beginning, middle, and the end. What is important to note is that events within the story are not only arranged in successive order, but also embedded with implied causality,[22] which could be understood as uniquely identified by an underlying temporality (structure of time) supplied by the narrator. Thus, the act of “Nesting” is to interconnect the corresponding units of two respective stories.[23] By “nesting”, the narrator is transposing the temporal structure or logic of one story onto the other. In our case,[24] Paul is transposing the temporal logic of the story of fallen angels from his contemporary apocalyptic literature into the story of Corinthians to support his judgement of the Corinthians. It is with respect to this direction that the following exegesis proceeds.

While the apostles are exhibited as the “actors”, their audiences include “the whole universe” which includes both angels and people.[25] The Corinthians then pertain to the category of “people”, who are listed alongside the angels because both share a kind of similitude: a similar narrative of employing their own wisdom for self-gratification. While §2.1 has demonstrated how problems arose from the narrative of the Corinthians themselves, the following will account for the stories of angels.

The Apocalyptic Narrative of the “ἀγγέλοις”

The English translation for the word “ἀγγέλοις” (4:9), angels, has been commonly understood as referring to good angels in modern time. Along a similar line of thought, some exegetes hold this positive stance because they argue that Paul could have used “principalities (ἀρχάς) and powers (ἐξουσίας)” for angels which are not good.[26] Nonetheless, such an argument suffers from the so-called “word and thing” approach, which neglects that a word could bear different meanings in different contexts.[27] In the following, I will demonstrate that “ἀγγέλοις”(4:9) could also refer to fallen angels subjected to Satan.

Firstly, while most commentaries do not provide detailed explanation on the words “ἀγγέλοις”(4:9), one particular scholar Chow does address the possibility of interpreting ἀγγέλοις as referring to evil spirits.[28] In fact, considering Paul’s own fourteen usages of “ἀγγέλος” in his writings, both good and evil angels have been referred to.[29] Among the 6 usages in Corinthians,[30] at least three times refer to the evil ones (1 Cor 4:9, 6:3; 2 Cor 12:7). Also, that Paul intentionally supplies the gentivie “φωτός” to modify “ἄγγελον” (2 Cor 11:4) aligns with the claim that when the words of “ἀγγέλος” are used alone, they could well refer to evil angels.[31] As Daniel Reids rightly observes: “the fact that the angels are listed with “the world” (κόσμῳ) and “humans” (ἀνθρώποις) could suggest that Paul had in mind inimical spirits.”[32] Hence, textual consideration at least does not eliminate the reading of “ἀγγέλοις” as evil angels.

Secondly, a continuity of thought between traditional Jewish apocalyptic thought, of which the Book of Watchers (1 Enoch 1-36) of Enochic tradition is concerned, and Paul’s ideas in Corinthians could be built to show that Paul probably understands “ἀγγέλοις” as evil ones.[33] During the first century, the Book of Watchers was not only considered authoritative by many Jews,[34] but it also enjoyed significant status in some Christian circles,[35] influencing the formation of the N.T.[36] Hence, it is at least probable that Paul was cognizant of this story during his writing of Corinthians.[37] While the authenticity of 1 Enoch, the subsequently non-canonical pseudepigraphon, is debatable and that not all of its content might serve as dogmatic and exegetical foundation, to a certain extant it does reflect the cultural ideology within Jewish apocalyptic thought of the Second Temple Judaism, from which Paul is not abstracted.[38] Within the two epistles to the Corinthians, identifiable salient apocalyptic elements include:[39]

- Eschatological dualism: the present age is evil but the salvific age is to come. (1 Cor 1:20, 2:6–7, 10:11; 2 Cor 5:7)[40]

- Spatial dualism: the earth is the realm where humans temporarily dwell; the eternal heaven, God and angelic being. (1 Cor 1:17, 8:5; 2 Cor 4:18, 5:1-5) (p32 Aune) (2 Cor 12:2)

- Ethical dualism: the Satan is the evil opponents to God and Christians (1 Cor 7:5; 2 Cor 2:11, 11:14; 12:7)

- Expectation of the resurrection of the righteous (1 Cor 15:20–23). Meanwhile, a similar expectation occurs in Enochic texts (1 Enoch 2 39:4–5; 62:15; 2 Enoch 65:10)

- Expectation of Jesus’ parousia as the apocalyptic scene (1 Cor 15:51–57)[41]

- Experience of receiving divine revelation (2 Cor 12:1-2; c.f. 1 Cor 4:1, 9:1)

Therefore, it is not untenable to construe 4:9-10 from an apocalyptic perspective. More precisely, it is quite reasonable to argue for the interpretation of “ἀγγέλοις” as evil angels as according to the Book of Watchers,[42] in which chaptes 6-11 clearly reflects an angelic interpretation of the “sons of God” in Genesis 6:1-4, giving rise to the Jewish tradition of fallen angels,[43] that later influenced even Josephus the historian (1.72). Hence, when Paul communicated with the Corinthians, his appropriation of his Jewish apocalyptic tradition is at least probable, as he also does in 2 Cor 11:15.[44] In addition, employing stories from Jewish tradition for exhorting is not uncommon for the N.T. authors because their readers were familiar with it or[45] see it as authoritative.

The third argument comes from the story in 1 Enoch. In the beginning of the story, when the sons of God, namely the angels, saw and lusted after the beautiful women of men (6:1-2), with whom they had sexual union, they defiled themselves and sinned against the Lord consequently (7:1-9:11). In the end, the Lord judged the fallen angels and promised an eschatological restoration (10:1-22). Throughout the story, mentions of wisdom and knowledge are noteworthy: the angels taught them various kinds of knowledge and wisdom (7:1-8:3). Is there a causal relationship between teaching of secret knowledge and wisdom and sexual immorality? Or is it a mere parallel description without any causality? On the one hand, a corollary is more probable to have been implied; on the other hand, there exists also a myth in Midrash[46] that mentions the angel Shemḥazai taught a woman Istahar in exchange for sex.[47] Hence, the evil angels in 1 Cor 4:9, who have been proposed as a better alternative to the good ones, could find their form of evils as revealing secret knowledge and wisdom to humans in exchange for sex[48].

Nesting the Angels’ Story to Corinthians’ story

The juxtaposing of “ἀγγέλοις” alongside “ἀνθρώποις” may also reflect Paul’s attitude in highlighting a certain similitude between them.[49] In particular, I argue that it is with respect to a sharing of similar storylines between “ἀγγέλοις” and “ἀνθρώποις” (i.e. The Corinthians) that allows Paul’s nesting of one’s story over another’s. However, nesting stories is not a mechanical way of making one story follow another strictly. I reckon that their interconnection between those two aforementioned stories is undergirded by various thematic resonances. In particular, they are the themes of wisdom, knowledge as well as sin. For both parties, wisdom and knowledge serve as their common points of departure. Just as the angels possessed mysterious knowledge and wisdom, the Corinthians perceived themselves as wise and valued wisdom (1 Cor 1:5-6; 8:1).[50] What is common between them is that they both misused their given knowledge,[51] resulting in their respective sins as mentioned in §3.1 and §3.2.

Another important to note is that the apocalyptic background about angels does match with the metaphor of θέατρον, wherein the angels are as if audience of the spectacle. According to the Jewish apocalyptic tradition (c.f. 1 Enoch 9:1), the angels had always been watching what was happening among humans.[52] This is probably the reason why they are called watchers in 1 Enoch, even after they sinned (1 Enoch 12:4; 15:2). Thus, these watching angels were juxtaposed alongside the Corinthians as the audience who “watches” the spectacle of the apostles.[53]

Their stories are nested and can be analyzed as below:

| Beginning | Middle | Ending | |

| Angels | possessed wisdom and knowledge | Misused wisdom and knowledge to sin | Were judged by God |

| Corinthians | Implied result | ||

| valued wisdom |

Nesting these two stories together juxtaposes also their common storylines and temporal structures. Thus, the theme of the angels’ story: wisdom-sin-judgment, is then transferred to that that of the Corinthians. More precisely, Paul is challenging the Corinthians: “the wisdom and knowledge that you possess is just like those of fallen angels instead of the divine, leading you astray to sin. You will be judged eventually.” Thereby, Paul not only refuted their wisdom, but also warned them that judgment for their sins will come upon them eventually. This strengthens his counter-argument against their criteriology of the divine, which perceived their success, abundance, and wisdom as God’s blessing due to their overly-realized eschatology..

3. Paul’s Argument for Foolishness

Another point of contestation arises from the Corinthians’s understanding of wisdom. On the one hand, Paul contested Corinthians’ narration of wisdom by nesting a story from Jewish apocalyptic tradition onto their narrative. On the other hand, facing the Corinthians’ misunderstanding about his apparent foolishness and weakness, He argued for his narration of foolishness by establishing his own criteriology: God’s true wisdom does appear as worldly foolishness. His first argument is that the apostles’ apparent foolishness and weakness will be shown as wise eventually. The second is established through a nesting of his own story onto that of Christ, which will be explained below in a three-step manner:[54] first, the resemblance between Christ and the apostles in the metaphor; second, the apocalyptic character of the epistles echoes with the reversal-notion of the metaphor; third, Paul’s own nesting of stories on the basis of the first and second.

The Metaphor of θέατρον

While part two in the above has focused on the identity of the audiences of Paul’s θέατρον, this part will focus on the content of the θέατρον (spectacle): How did God exhibit the actors as a spectacle?[55] What did the actors play? The answer proposed here is that it is a deathly spectacle resembling the crucifixion of Christ,[56] and hence the story of Christ.

Most scholars have endeavoured to identify the historical reference of the metaphors by taking the antecedent “ἐσχάτους… ὡς ἐπιθανατίους”(4:9) and the postcedent “ἡμεῖς μωροὶ διὰ Χριστόν”(4:10) into account. While “ἐσχάτους” is understood as referring to those who were placed last in either triumphal procession[57] of Roman army or march-in[58] in the arena; “ἐπιθανατίους” is understood as referring to the gladiators[59] who were previously criminals[60] or captives.[61] Considering the postcedent, Larry Welborn uniquely suggests mime performance[62] on the basis of his historical-cultural investigation and Paul’s usage of “μωροὶ”.[63]

However, according to Ricoeur’s understanding of metaphor, identifying an exact historical reference does not fully explain the understanding of a metaphor. According to Ricoeur, a metaphor is a verbal icon that schematizes a plenitude of images,[64] whose tension sustains the life of a metaphor.[66] Hence, as Friesen aptly opines, “several modes of performance other than a single one are encompassed”, particularly, “in the Paul’s term “θέατρον”,[67] on which Friesen has mainly focused. In other words, “θέατρον”(spectacle) is the integratory key, or the root metaphor in Ricoeur’s term, that gives rise to productive imagination schematizing the other two metaphors,[68] notably “ἐσχάτους… ὡς ἐπιθανατίους”.[69] Therefore, Paul was actually projecting a spectacle to the Corinthians, wherein the apostles were as if condemned to death, the last, and fool – different attributions are interconnected in a metaphorical network.[70] How does a connection to Christ be built through this metaphor?

In the first chapter of the epistle, Paul has already preached the crucified Christ which is foolishness to the Gentiles (1:23). Here it is evoked again when he mentioned “we are fools for Christ”(4:10) on the basis of the hook-words: “fool” and “Christ”.[71] Following the same vein, the apostles (4:11-13) were depicted in a manner similar to that of Christ; treated like Jesus, they responded like Jesus.[72] This parallel also aligns with the expression of “ἐσχάτους… ὡς ἐπιθανατίους” since Jesus was also one whom was condemned to death[73] and publicly executed as a spectacle.[74] Such proximity between the apostles and Christ allows Paul for a nesting of their stories.

In addition, Ricoeur’s notion of metaphor also allows the inclusion of the metaphorical network within the discourse of contestation. According to Ricoeur, the referential function[75] and meaning of metaphors are to project another “inhabitable world” for the Corinthian readers to live,[76] redescribing their reality,[77] and causing a shock to them.[78] It therefore aligns with the notion of contestation: it’s Paul’s proposed world versus the reader’s world; Paul’s redescription v.s. a Corinthians’ previous description.

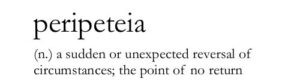

Apocalyptic Reversal in the Theatre

The metaphorical network has also laid the foundation for innovating resemblance between Christ and the apostles. In a larger sense, it provides a temporal storyline that further strengthens their proximity, as “θέατρον” functions as the metaphor in which a reversal of the present suffering experience of the apostles is implied. It is Friesen who uniquely argues that Paul resorted to the contemporary tragic drama to construct the metaphor[79] on the basis of his investigation of the theatrical culture[80] in the mid-first-century in both Judea and Corinth. He indicates that tragedies commonly have “reversals” (περιπέτεια) or deus ex machina as central to their plots. More precisely, he highlights that the apparent foolishness turns into true wisdom at the last stage of the drama.[81] In the same manner, the way Paul situated the apostles, including himself, in this metaphor was implied a similar reversal in their narrative: their current plight and suffering (4:11-13) will be intervened and changed eventually.

This suggestion at least echoes with three themes within the apocalyptic aura pervading in 1 Corinthians (§2.3). Firstly, in tandem with the temporal dualism of contemporary apocalypticism, this age was generally pictured as evil while hope was placed on God’s eschatological intervention, bringing upon God’s judgment, annihilation of evil, and inauguration of the eternal future age.[82] Through the nesting of narratives between the Corinthians and the angels as explained in the above, the theme of eshcatological judgment can be envisaged. Secondly, the suffering and plight of the apostles that Paul depicted echoes with the theme – “imminent crisis” among apocalyptic literature.[83] Paul did not blindly transpose the apocalyptic literature into the epistles, replicating neither a political persecution nor post-exilic hardship as Israel had faced.[84] His focus is firmly on the plight and suffering of the apostles.[85] The third theme is the “faithful remnant” who are characterized as those resisting evil and serving God. They are those who rejected the social and religious status-quo, as well as the apostate culture around them.[86] Taylor particularly notes that the remnant theme points to an eventual reversal of the injustices of this life.[87] It is proposed that the apostles bore similarity with the faithful rammants in the sense of rejecting the contemporary Corinthian culture.[88] Therefore, the apocalyptic soil does allow the possibility of fertilizing a theatrical metaphor implying a reversal that will happen to the apostles.

Nesting with Christ’s story

With the content of the deathly spectacle exhibiting the temporal storyline of a reversal, we can see how Paul nested his story onto that of Christ.[90] On one hand, He could reverse believers’ story because He is the Messiah[91] who rescues them from the present evil age into liberation of the new age.[92] On the other hand, He is the one whose story is eventually reversed by God[93] since the apocalyptic triumph of God proleptically has been realized in Christ.[94] Therefore, regarding the epistle, there are exegets who observe that “Paul’s strategy is to encourage the Corinthians to understand themselves in terms of an apocalyptic narrative that locates present existence in between the cross and parousia.”[95] In other words, Christ’s event constitutes the apocalyptic narrative for believers to orient themselves, and it is exploited by Paul to establish his argument. Therefore, the story of Christ not only resonates with the theatrical reversal in the metaphor but also is consistent with the apocalyptic character mentioned.

The way Paul nested stories can be analyzed as below:

| Beginning

(the past) |

Middle

(the present) |

Ending

(the future) |

|

| Christ | They were both appointed by God. | Both were mistreated and perceived as foolish. | Glorified and honored by God |

| The apostles including Paul | Implied result |

By nesting his story implicitly with that of Christ, Paul was implying a reversal that will happen to the “foolish, weak, poor” apostles, as happened in the Jewish apocalyptic literature and to Christ, as well as in the Hellenistic drama. All these elements are intertwined to construct support for establishing his criteriology of the divine, simultaneously, countering that of Corinthians, which is corrupted by success and wisdom. Paul was claiming: “I might have looked foolish and weak, suffering greatly but these experiences stand alongside the divine as Christ does.” More precisely, he intends that being worldly foolish could be the divine predicate. That is also why Paul mentioned that God is who exhibited them (4:9), he was ascribing his present hardship to the divine to defend for his own status-quo, which seems God-forsaken to the believers who misunderstood their faith with over-realized eschatology.

Conclusion

I divide this essay into two parts to answer the main research question: “why are the angels included among the watchers of the spectacles wherein God has exhibited the apostles the last, as those condemned to death?” On the one hand, part 2 has demonstrated that Paul attacked the Corinthians’ criteriology of the divine by rebuking their self-perception of wisdom through nesting the apocalyptic narrative of the fallen angels onto them. On the other hand, part 3 explains that Paul established his own criteriology by rectifying the misconception of foolishness. His strategy consists of employing a theatrical metaphorical network, wherein the apostles are situated, and nesting his story into that of Christ – these are conducted within the apocalyptic background, which serves as the integratory key to his strategy. Thereby, Paul argued that his apparent foolishness and weakness were actually God’s wisdom because a reversal would happen to him as to Christ, as in apocalyptic narratives, as in θέατρον.

Bibliography

Adams, Sean A. ‘Paul, the fool of Christ: a study of 1 Corinthians 1 – 4 in the comic-philosophic tradition’. Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism. Journal for the study of the New Testament Supplement series Early Christianity in context (2007): 89–91.

Aharon Varady. ‘The Mythic Arc of Predatory Desire in Jewish Legend’, 2016. http://aharon.varady.net/omphalos/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/The-Mythic-Arc-of-Predatory-Desire-in-Jewish-Legend-Aharon-Varady-v.2.2.pdf.

Annus, Amar. ‘On the Origin of Watchers: A Comparative Study of the Antediluvian Wisdom in Mesopotamian and Jewish Traditions’. Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 19, no. 4 (June 2010): 277–320.

Aune, D. E. ‘Apocalypticism’. Edited by Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid. Dictionary of Paul and His Letters. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993.

Bauckham, Richard. ‘Moltmann’s Theology of hope revisited’. Scottish Journal of Theology 42, no. 2 (1989): 199–214.

Carey, Greg, and L. Gregory Bloomquist, eds. Vision and persuasion: rhetorical dimensions of apocalyptic discourse. St. Louis, Mo: Chalice Press, 1999.

Ciampa, Roy E., and Brian S. Rosner. The first letter to the Corinthians. The Pillar New Testament commentary. Grand Rapids, Mich. : Nottingham, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ; Apollos, 2010.

Cline, Rangar. Ancient angels: conceptualizing angeloi in the Roman Empire. Brill, 2013.

Collins, John J. ‘Books of Enoch’. Dictionary of New Testament Background. Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2000.

DeSilva, David Arthur. An introduction to the New Testament: contexts, methods & ministry formation. Downers Grove, Ill. : Leicester, England: InterVarsity Press ; Apollos, 2004.

———. Introducing the Apocrypha: message, context, and significance, 2018.

Dunn, James D. G. The theology of Paul the Apostle. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmanns, 2008.

Dunnett, Walter M. ‘The Hermeneutics of Jude and 2 Peter: The Use of Ancient Jewish Traditions’. journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 31, no. 3 (1988): 287–292.

Fodor, James. Christian hermeneutics: Paul Ricœur and the refiguring of theology. Oxford : New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, 1995.

Friesen. ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’. Journal of Biblical Literature 134, no. 4 (2015): 813.

Hafemann, Scott J. ‘Paul and His Interpreters’. Edited by Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid. Dictionary of Paul and His Letters. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993.

Hays, Richard B. The faith of Jesus Christ: the narrative substructure of Galatians 3:1-4:11. 2nd ed. The biblical resource series. Grand Rapids, Mich. : Dearborn, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans ; Dove Booksellers, 2002.

Nguyen, V. Henry T. ‘The Identification of Paul’s Spectacle of Death Metaphor in 1 Corinthians 4.9’. New Testament Studies 53, no. 4 (October 2007): 489–501.

Reed, Annette Yoshiko. ‘The Parting of the Ways? Enoch and the Fallen Angels in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity’. In Fallen angels and the history of Judaism and Christianity: the reception of Enochic literature, 122–159. Cambridge University Press, 2009.

Reid, Daniel G. ‘Angels, Archangels’. Edited by Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid. Dictionary of Paul and His Letters. Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993.

Ricœur, Paul. The rule of metaphor: multi-disciplinary studies of the creation of meaning in language. Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 1981. http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/417319.

Ricoeur, Paul. Time and Narrative. Translated by Kathleen McLaughlin. Vol. 1. 3 vols. Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2009.

Robertson, Archibald, and Alfred Plummer. A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians. 2nd ed. T & T Clark, 1971.

Stiver, Dan R. Ricoeur and theology. Philosophy and theology. London: Bloomsbury, 2012.

Taylor, Mark. 1 Corinthians. Edited by E. Ray Clendenen. Vol. 28. The New American Commentary. Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2014.

Thiselton, Anthony C. New horizons in hermeneutics. Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan Pub. House, 1992.

Thiselton, Anthony. ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’. Neotestamenica 40, no. 2 (January 1, 2006): 320–352.

Trail, Ronald L. Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9. 2nd ed. Exegetical summaries. Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2008.

Welborn, Laurence L. Paul, the fool of Christ: a study of 1 Corinthians 1 – 4 in the comic-philosophic tradition. Journal for the study of the New Testament Supplement series Early Christianity in context 293. London: T & T Clark Internat, 2005.

Yip, Ying Lam. ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’. Ph.D., University of Exeter, 2019. http://hdl.handle.net/10871/37426.

克雷格.布魯姆伯格著。尹妙珍譯。《哥林多前書》。國際釋經應用系列。香港:漢語聖經協會,2002。

周天和。周天和主編。《哥林多前書》。第34冊。1版。中文聖經註釋。香港:基督教文藝出版社,2001。

奧斯邦著。劉良淑 and 李永明譯。《21世紀基督教釋經學: 釋經學螺旋的原理與應用》。新北市:校園書房,2012。

張永信。《哥林多前書》。明道研經叢書。香港:明道社有限公司,2010。

張略 and 張永信。《彼得前書》。台北:天道聖經註釋,1997。

張達民 and 何善斌。《哥林多前書(卷下)》。香港:天道書樓,2002。

莫理斯著。蔣黃心湄譯。《哥林多前書》。丁道爾新約聖經註釋。台北:校園書房,1992。

黃根春。《基督教典外文獻:舊約篇 (第一冊)》。香港:基督教文藝出版社,2002。

黃浩儀。《哥林多前書(卷上)》。天道聖經註釋。香港:天道書樓,2018。

Notes

- Anthony C. Thiselton, New horizons in hermeneutics (Grand Rapids, Mich: Zondervan Pub. House, 1992), 355.; Ying Lam Yip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’ (Ph.D., University of Exeter, 2019), 72, http://hdl.handle.net/10871/37426. ↑

- It is almost a consensus shared by scholars that Ch.1-4 belongs to the same exegetical unity handling the ecclessial division and quarrel. NAC 23: Taylor notes that the wisdom of God over against human wisdom is an overarching theme of the section in 1:10–4:21. Also, he writes that all expound the nature of the gospel as divine wisdom over against human wisdom since the latter lies at the source of their divisions (1:18–4:13). Mark Taylor, 1 Corinthians, ed by. E. Ray Clendenen, vol. 28, The New American Commentary (Nashville: Broadman & Holman Publishers, 2014), 23, 48.; Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, Journal of Biblical Literature 134, no. 4 (2015): 819.; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格著,尹妙珍譯:《哥林多前書》。國際釋經應用系列(香港:漢語聖經協會,2002),頁25。; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》。天道聖經註釋(香港:天道書樓,2018)。 ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:115. ↑

- James D. G. Dunn, The theology of Paul the Apostle (Grand Rapids, Mich.: Eerdmanns, 2008), 347. ↑

- Anthony Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, Neotestamenica 40, no. 2 (January 1, 2006): 325–327, 321–323.; David Arthur DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament: contexts, methods & ministry formation (Downers Grove, Ill. : Leicester, England: InterVarsity Press ; Apollos, 2004), 555–557. ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:19. ↑

- Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 327. ↑

- DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament, 566. ↑

- Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 331.; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁21。; Daniel G. Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, ed by. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters (Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 21.; 張永信:《哥林多前書》。明道研經叢書(香港:明道社有限公司,2010),頁21。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:44. It is noted that Mark Taylor holds a different view, “every Corinthian problem was not due to their “over-realized eschatology.” ↑

- 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94–95。 ↑

- Yip has explained it as the usual criterion of the discernment of God’s action see his footnote no. 170. Yip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’, 101.; Dan R. Stiver, Ricoeur and theology, Philosophy and theology (London: Bloomsbury, 2012), 129. ↑

- Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 323. ↑

- Yip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’, 101. ↑

- 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁18–21。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94。 ↑

- Mark Taylor notes that the first Corinthians is Paul’s response both to what he had heard about the church and to the content of their letter to him. Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:21, 99.; DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament, 565.; Wong notes that the Corinthians even openly criticized the apostles. 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁246。 ↑

- Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 320, 330.; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁18。 ↑

- DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament, 566.; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁56。 ↑

- Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 320, 322–323.; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁18。 ↑

- It is noted that Mark Taylor does not agree with the interpretation of the “overly realized eschatology” of the Corinthians, he observes that 4:8 as their point of view. 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁242–245。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁19,94。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:116. ↑

- DeSilva has noted that Paul turned this way of thinking, evaluating and competing on its head by focusing on the mystery of the cross and on the abundance of God’s generosity. DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament, 567. ↑

- The idea of nesting of stories appropriated here for exegesis owes credit to the thesis of Yip. My introduction and explanation of this concept are situated at the beginning of §2.2. For details, seeYip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’, 83–86. ↑

- Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative, trans by. Kathleen McLaughlin, vol. 1 (Chicago, Ill: University of Chicago Press, 2009), 69. As Ricoeur observes, the ordering of events and the causal connection (one thing as a cause of another) prevails over pure succession. ↑

- Yip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’, 84. ↑

- Yip, ‘Contestation of testimonies : a narrative analysis of identity formation in Philippians’, 85. ↑

- Considering NA28: “τῷ κόσμῳ καὶ ἀγγέλοις καὶ ἀνθρώποις”, since “ἀγγέλοις” καὶ “ἀνθρώποις” are not articular, they are understood as pertaining to the articular “τῷ κόσμῳ”. 周天和,周天和主編:《哥林多前書》,第34冊,1版。中文聖經註釋(香港:基督教文藝出版社,2001),頁143–144。; 張永信:《哥林多前書》,頁95。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:122. ↑

- Ronald L. Trail, Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9, 2nd ed., Exegetical summaries (Dallas, TX: SIL International, 2008), 172. ↑

- This method assumes that the word as the symbol is identical with the things referred. 奧斯邦著,劉良淑及李永明譯:《21世紀基督教釋經學: 釋經學螺旋的原理與應用》(新北市:校園書房,2012),頁123。 ↑

- The author, Chow, has simultaneously listed both sides of view while he himself remained reserved to make judgments. 周天和:《哥林多前書》,34:頁144。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, vol. 28, p. .; 張永信:《哥林多前書》。; 莫理斯著,蔣黃心湄譯:《哥林多前書》。丁道爾新約聖經註釋(台北:校園書房,1992)。 ↑

- Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, 20. ↑

- The other two are 1 Cor 11:10; 13:1, which mention “because of the angels” and “the tongues of mortals and of angels.” Mark Taylor sees that 1 Cor 11:10 better refers to the way angels cover their head (c.f. Is 6:2) in worshipping the Lord. (p.263). Hence, this verse is tentatively considered as a positive reference. ↑

- It is noteworthy that the ἀγγέλοις is Not articular in 1 Cor 4:9. Therefore, even.A. Robertson and A. Plummer submit that the fallen angels’ view is “somewhat childish”, their argument on the basis of the article is not strong enough. They thought that the articular “the angels” always refers to good angels, see Archibald Robertson and Alfred Plummer, A Critical and Exegetical Commentary on the First Epistle of St. Paul to the Corinthians, 2nd ed. (T & T Clark, 1971), 233. ↑

- Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, 21. ↑

- Ho Sin-Pan points out that the doctrine of angels and demons is one of the characteristics of the Second Temple Judaism, which influences Paul deeply. In addition, not only Paul, but Jude also receives Enochic tradition as well. For example, he directly quoted 1 Enoch 60:18 (Jude 14). Walter M. Dunnett, ‘The Hermeneutics of Jude and 2 Peter: The Use of Ancient Jewish Traditions’, journal of the Evangelical Theological Society 31, no. 3 (1988): 289.; David Arthur DeSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha: message, context, and significance, 2018, 28.; 張達民 and 何善斌:《哥林多前書(卷下)》(香港:天道書樓,2002),頁19–20。 ↑

- Annette Yoshiko Reed, ‘The Parting of the Ways? Enoch and the Fallen Angels in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity’, in Fallen angels and the history of Judaism and Christianity: the reception of Enochic literature (Cambridge University Press, 2009), 126–127. ↑

- John J. Collins, ‘Books of Enoch’, Dictionary of New Testament Background (Downers Grove: InterVarsity Press, 2000), sec. 4. ↑

- Collins, ‘Books of Enoch’, sec. 4.; 黃根春:《基督教典外文獻:舊約篇 (第一冊)》(香港:基督教文藝出版社,2002),頁5。 ↑

- Collins, ‘Books of Enoch’, sec. 4.; Reed, ‘The Parting of the Ways? Enoch and the Fallen Angels in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity’, 128. ↑

- Reed, ‘The Parting of the Ways? Enoch and the Fallen Angels in Rabbinic Judaism and Early Christianity’, 122–123. ↑

- D. E. Aune, ‘Apocalypticism’, ed by. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters (Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 31–32. ↑

- in 2 Cor 5:17, Paul uses the phrase “new creation,” a phrase with apocalyptic associations, see Aune, ‘Apocalypticism’, 31. ↑

- Aune, ‘Apocalypticism’, 31. ↑

- In addition, though the possibility that the readers could interpret “ἀγγέλοις” as referring to other spiritual being has also been considered, given Paul had spent sufficient time in Corinth shepherding the believers (Acts 18:11), it is not untenable to assume that Paul and the Corinthians share the same semantics in communication, namely the fallen angels. Besides, since Clines indicates that angels only became a significant aspect of religion in the late Roman Empire, the semantics is more probable to bear a Jewish meaning. Rangar Cline, Ancient angels: conceptualizing angeloi in the Roman Empire (Brill, 2013), 2. ↑

- Since Mark Taylor cites the comment of the exegetes of ICC in his footnote which disfavours the angelic interpretation, it is more likely that Taylor does not agree with such an interpretation as well. Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:263. ↑

- In 2 Corinthians 11:5, Paul also appropriated the Jewish tradition of Satan disguising himself (cf. Life of Adam and Eve 9; T. Job 6:4) and applies it to his opponents at Corinth who had disguised themselves as apostles (2 Cor 11:15), maintaining that they are ministers of Satan. Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:486.; Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, 22. ↑

- This is the view of Luke Cheung (張略) towards the way Jude cited 1 Enoch, which is transferable to reason why Paul resorted to the angels’ stories in Enochic tradition. DeSilva adds that Jude “regarded it as a valuable resource for the exhortation and edification of Christians, a suitable quotation from an ancient authority to advance his rhetorical goals, a text that would be expected to provide authoritative support for his.” (p.31)張略及張永信:《彼得前書》(台北:天道聖經註釋,1997),頁41。; DeSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha, 31.; DeSilva, Introducing the Apocrypha, 105. ↑

- Midrash Abkir (Hebrew: מדרש אבכיר) is one of the smaller midrashim ↑

- Aharon Varady, ‘The Mythic Arc of Predatory Desire in Jewish Legend’, 2016, 5–6, http://aharon.varady.net/omphalos/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/The-Mythic-Arc-of-Predatory-Desire-in-Jewish-Legend-Aharon-Varady-v.2.2.pdf. ↑

- Amar Annus, ‘On the Origin of Watchers: A Comparative Study of the Antediluvian Wisdom in Mesopotamian and Jewish Traditions’, Journal for the Study of the Pseudepigrapha 19, no. 4 (June 2010): 291. ↑

- Leon Morris sees that angels and people function as merism to include all personal beings (p.84). In this sense, those two words still bear similitude as they function as two different polarities in merism. Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, 21.; 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁84。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁36–37。 ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:42, 116.; 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁45。 ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:42–43. ↑

- 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁126,247。; 周天和:《哥林多前書》,34:頁144。; 張略 and 張永信:《彼得前書》,頁12。 ↑

- Reid, ‘Angels, Archangels’, 21. ↑

- Readers must note that two arguments are intertwined with Paul’s metaphorical network and apocalypticism that a clear causal dissection is not possible. ↑

- According to Ronald L. Trail (p.171-172), the “ὅτι” connecting the antecedent “God has exhibited us apostles as last of all, as though sentenced to death” and “we have become a spectacle” can be rendered as (1) because, for, or since, showing an effect-reason relationship, or (2) so that, showing a purpose. Either possibility does not hamper the current discussion and argument to a significant extent. What concerns are the apostles becoming a spectacle and God has exhibited them the last. Trail, Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9, 171–172. ↑

- V. Henry T. Nguyen, ‘The Identification of Paul’s Spectacle of Death Metaphor in 1 Corinthians 4.9’, New Testament Studies 53, no. 4 (October 2007): 501.; Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 814.; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:121. ↑

- NAC adopts the interpretation of NIV (P.121). 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:121.; 周天和:《哥林多前書》,34:頁143。 ↑

- 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁83。; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁225。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94。; 張永信:《哥林多前書》。 ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:121–122. ↑

- 張永信:《哥林多前書》,頁95。; Nguyen, ‘The Identification of Paul’s Spectacle of Death Metaphor in 1 Corinthians 4.9’.; 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁83。 ↑

- 周天和:《哥林多前書》,34:頁143。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94。 ↑

- Laurence L. Welborn, Paul, the fool of Christ: a study of 1 Corinthians 1 – 4 in the comic-philosophic tradition, Journal for the study of the New Testament Supplement series Early Christianity in context 293 (London: T & T Clark Internat, 2005). ↑

- Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 823.; Nguyen, ‘The Identification of Paul’s Spectacle of Death Metaphor in 1 Corinthians 4.9’, 493.; Sean A. Adams, ‘Paul, the fool of Christ: a study of 1 Corinthians 1 – 4 in the comic-philosophic tradition’, Journal of Greco-Roman Christianity and Judaism, Journal for the study of the New Testament Supplement series Early Christianity in context (2007): 89–91. ↑

- James Fodor, Christian hermeneutics: Paul Ricœur and the refiguring of theology (Oxford : New York: Clarendon Press ; Oxford University Press, 1995), 160–161. ↑

- Fodor, Christian hermeneutics, 155, 169. ↑

- Paul Ricœur, The rule of metaphor: multi-disciplinary studies of the creation of meaning in language (Toronto, Ont.: University of Toronto Press, 1981), 253, http://www.deslibris.ca/ID/417319. ↑

- Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 822. ↑

- Fodor, Christian hermeneutics, 162. ↑

- Trail, Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9, 170.; 張永信:《哥林多前書》,頁95。; 克雷格.布魯姆伯格:《哥林多前書》,頁94。; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁225。; 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁83。 ↑

- Fodor, Christian hermeneutics, 162. ↑

- Taylor notes the contrast between the apostles and the Corinthians echoes previous themes in 1:18–2:5 and 3:18–19.(p.122) Ronald Trail cites from ICC, indicating the foolishness of the apostles connects with Christ (p.171)Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:122.; Trail, Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9, 171.; Roy E. Ciampa and Brian S. Rosner, The first letter to the Corinthians, The Pillar New Testament commentary (Grand Rapids, Mich. : Nottingham, England: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Co. ; Apollos, 2010), 182. ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:122.; 周天和:《哥林多前書》,34:頁147–148。; Ciampa and Rosner, The first letter to the Corinthians, 18.; 張永信:《哥林多前書》,頁97。 ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:121. ↑

- Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 821. ↑

- Fodor, Christian hermeneutics, 162. ↑

- Ricœur, The rule of metaphor, 106. ↑

- Stiver, Ricoeur and theology, 71. ↑

- Stiver, Ricoeur and theology, 139. ↑

- Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 827–830. ↑

- 813-819. Notably, about one kilometre from the centre of the city to the east and north, there was an amphitheatre in the plan of the Roman colony (p.815). Jews encountered the theatre not only in the diaspora but also in Palestine, where Herod had theatres con- structed, thus making the performance of Greek drama available even at the geographical heart of Judaism (p.817). Friesen resorts to the popularity of not only the performance in which tragedy was played but also the tragic text (p.817-818). Friesen, ‘Paulus Tragicus: Staging Apostolic Adversity in First Corinthians’, 813–819. ↑

- Friesen particularly cites Euripides’s Bacchae and Sophocles’s Oedipus tyrannus. Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:79–80. ↑

- Richard Taylor also notes that God will turn the present worldly crisis and cruel acts of human evil into a cataclysmic supernatural victory. (p.66) He quotes 1 Enoch, 2 Baruch and 4 Ezra as examples. (p.81-85). Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:81–85.; Richard Bauckham, ‘Moltmann’s Theology of hope revisited’, Scottish Journal of Theology 42, no. 2 (1989): 19. ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:79–80. ↑

- Greg Carey and L. Gregory Bloomquist noted that Apocalyptic discourse does not link exclusively with oppressed communities and situations, oppression is still a salient theme for Paul to utilize in constructing his arguments. Also, the governmental persecution here is only an example for this theme, referring to the crisis ofHellenization under Antiochus, see Bauckham on page 15 and 19. Greg Carey and L. Gregory Bloomquist, eds., Vision and persuasion: rhetorical dimensions of apocalyptic discourse (St. Louis, Mo: Chalice Press, 1999), 6–7.; Bauckham, ‘Moltmann’s Theology of hope revisited’, 15, 19. ↑

- Hence, the way Paul echoes with apocalyptic tradition exhibits similarity rathern than identity. Besides, Ciampa and Rosner indicate that catalogues of hardship are not only common in Pauline epistles but also appear in other ancient writings, of which Jewish apocalypse is included. Ciampa and Rosner, The first letter to the Corinthians, 180.; 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁249。 ↑

- Though Taylor illustrates this theme with both 4 Ezra and Daniel, only the latter is considered as influencing Paul in writing this epistle . Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:80–81. ↑

- Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:81. ↑

- This notion is based on the historical-cultural investigation of deSilva that highlights the contrast between the apostles against contemporary culture. Few examples include: firstly, Paul decided not to play to the cultural expectations of sophists and orators (p.562); Paul refused to accept patronage from anyone of his congregation lest being misunderstood as his client who competed for honor (p.564) Instead, he preached the cross against the conventional wisdom and notions of power and status. (p.567). Thiselton 329 also notes that the cross Paul preached can have only the inevitable effect of subverting and reversing the value-system that dominated Corinthian culture. Thiselton, ‘The significance of recent research on 1 Corinthians for hermeneutical appropriation of this epistle today’, 329.; DeSilva, An introduction to the New Testament, 562, 564, 567. ↑

- Morris and Trail indicate that the logic behind this is that the present suffering of the apostles serves as counter-evidence against the eschatological reign of Christians. Thus, the Corinthians actually had not reigned as kings as they thought. (c.f. 4:8) For Mark Taylor, he notes the emphasis on the “present” is parallel to the three “alreadys”. 黃浩儀:《哥林多前書(卷上)》,頁250。; Trail, Exegetical summary of 1 Corinthians 1–9, 175.; 莫理斯:《哥林多前書》,頁85。; Taylor, 1 Corinthians, 28:122. ↑

- Scott J. Hafemann, ‘Paul and His Interpreters’, ed by. Gerald F. Hawthorne, Ralph P. Martin, and Daniel G. Reid, Dictionary of Paul and His Letters (Downers Grove, Ill: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 677. ↑ Furthermore, the consistency of this set of notions can be better validated if the apocalyptic character of Christ’s story in Paul’s perception is noted. As Beker insightfully opines, “Paul geniusly correlated and applied the overarching and consistent apocalyptic theme to various and distinct situations, without dissolving the coherence of the gospel” of Christ.

- Aune, ‘Apocalypticism’, 29–30, 33. ↑

- Richard B. Hays, The faith of Jesus Christ: the narrative substructure of Galatians 3:1-4:11, 2nd ed., The biblical resource series (Grand Rapids, Mich. : Dearborn, Mich: W.B. Eerdmans ; Dove Booksellers, 2002), xxxix. ↑

- Paul has reflected his thinking in 1 Corinithians 15:25-28; 57; c.f. Philippians 2:8-11. ↑

- Hafemann, ‘Paul and His Interpreters’, 677. ↑

- Ciampa and Rosner, The first letter to the Corinthians, 180. ↑

即將畢業的神學生。既然去不到日本旅行,就暫且戀棧在書本的文本世界中遊走。

所以,寫作功課是遊記,整理思緒去過的地方,又再探索創作新的可能性。

得閒一齊飲啡 ☕