- Part 1: Stacking stories from ancient to present…

- Part 2: Threefold Mimesis in explaining Saul vs. Paul

- Part 3: Threefold Mimesis on the Philippian Church

- Part 4: What is the implication?

After seeing the framework of the Dunn’s Five-Level of Story Model on the previous page, we would see further on how the concept of “Threefold Mimesis” suggested by Paul Ricoeur’s narrative theory working together.

Saul vs Paul

Mimesis 1

For the study of “the Story of Paul”, we would mainly focus on the testimony of Paul in Phil 3:4-16. To begin with, we would study the temporal identity of Saul the Pharisee. As his introduction in Phil 3:5, he was in the narrative identity of the people of Israel with the circumcision on the eight day of the birth, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Hebrew born of Hebrews; as to the law a Pharisee. In terms of ethical identity, he was zealous for Torah in the way of persecuting the churches of Christ as he stood on the side of Torah which he learned from Gamaliel (Act 22:3-4), and what he behaved were blameless according to Torah (Phil 3:6). His zealous was a kind of martyrdom.

Death and Martyrdom

In first-century Judaism, the sacrificial system had been shifted the focus from the element of “blood” sanctification and “covenant” to the concept of “obedience” to demands of Yahweh revealed in the Torah.[1] Yet, “obedience” would face two challenges: 1) suffering of the righteous, obedience to the Torah did not secure immunity from the outrageous fortune as “Book of Job” and “Psalms” in OT demonstrated. 2) court suffering and death would come if oneself take the yoke of Torah which was incompatible to that of the authorities of this world. Judaism termed these issues as “martyrdom”.[2] The latter challenge was the main stream that “obedience to Torah , suffering unto death” was regarded as the destiny of the martyr, especially for martyrdom for the sake of Torah which was regarded as the acme of obedience in first-century Judaism. The obedience to the Torah was usually occurred in either way: 1) resorting to arms like rebellion of “Maccabean martyrs”; 2) passive acceptance of death out of loyalty to the revealed will of God as the crown of loyalty to the Torah as the character of “Assumption of Moses”.[3] In the society of Graeco-Roman, Judaism could enjoy the benefit from the government policy,[4] so Saul the Pharisee, as the member of the parties enjoying the benefit from government, he would not have to resist to the government, but would be zealous to persecute and arrest the followers of the Way of Jesus into prison. (Act 22:4) The extend to which Saul was crazy for the Torah, would pertain as a martyr for Torah.

Mode of Death

For the incident of Christ’s death, Saul, as many Pharisee, believed that Jesus was the one who blasphemed God which was under consensus of chief priests, with elders, the teachers of laws (i.e. including Pharisee) and the Sanhedrin (c.f. Mark 14:53-65; Mat 26:57-68; Luk 22:54-55, 63-71; Joh 8:13-14, 19-24). And also perhaps, the consequence of Jesus who was trial by the governor (i.e. Pilate) (c.f. Mark 15:1-15; Mat 27:1-2, 11-126; Luk 23:1-5, 13-25; Joh 18:28-19:16) and crucified (c.f. Mark15:21-32; Mat 27:32-44; Luk23:26-43; Joh 19:17-27) which was used in executing slaves and heavy criminals[5] who were regarded as morally or socially disparage in general citizens in the contemporary world. For Jews, the crucifixion symbolized as a curse in Deut 21:22-23. Although a cross was not a pole, and trees were often used for crucifying convicts.[6] This also implied the victim was outside the pale of Israel.[7] Rabbi even concern about the “mode of death”. According to the Rabbinic thoughts in first two century, “to be slain” by sword in the same way as murderers and desecrators of the Sabbath, would imply commit a grievous sin. This was their real pain but not the suffering inflicted.[8] Thus, we could imagine what all people and Saul would regard that “the Story of Jesus Christ” would be a failing and shameful one, and would not be a martyrdom story. This is the “general narrative background or preunderstanding of human action” [9] before Paul’s encountering with Christ.

Eschatological Resurrection concept

It is believed that the first century Judaism influenced by two main streams in the eschatological aspects:[10] Messianic Kingdom[11] and Danielic eschatology.[12] Both aspects were being harmonized into a framework composed of: this Present Age (hâ-‘ôlâm hâ-zeh), the Messianic Era, the Age to Come (hâ-‘ôlâm ha-bâ’). Traditional apocalyptic convention was proposed that only those alive at the Advent of the Messiah should participate in Messianic Age, and the resurrection was placed at the end of Messianic Kingdom or at the beginning of the “Age to Come”. Simply speaking, just like other Jewish, Saul would believe that general resurrection and the advent of judgement would only happen on the “Age to Come”, and he would conceive of it as a final consummation of all created being,[13] and enter into Paradise. And also, he would still be disembodied until the resurrection, although participating in blessedness.[14] By that time, Saul had not recognized Jesus Christ.

This is the world that Saul was facing, and the Philippian’s citizen as well. It would be no sense to suffer for the Gospel of Jesus, and of course, it would be absurd before they recognized Jesus Christ. These background and preunderstanding are the “Prefiguration” which is named as Mimesis 1 under Ricoeur’s terminology. If we confine into the testimony, Phil 3:4-6 would be regarded as Mimesis 1 of Paul’s later transformed story. Of course, there would be earthly social imperial factors, such as the imperial cult, the privilege of Judaism and the “patronage system”, which would be elaborated in the section 2.2.1. All these piled up a protective privilege.

Mimesis 2

To Saul, the encountering of Christ in Damascus (Act 9:3-6; 22:6-10) was just like a person starting to open a book which was already in place awaiting him. Here, in the epistle of Philippians, did not narrate the story details, but the clause of “To know Christ that is the power the resurrection of Him” in Phil 3:10a-b implied the continuous experiencing the power started after this encountering happened, and the usage of rarely phrase “τὴν δύναμιν τῆς ἀναστάσεως αὐτου”, which could be reasoned as “God’s power that raise up Christ” recall the exaltation in Christ’s story/event (Phil 2:9).

In this stage, the process of “discordant concordance” as Ricoeur described,[15] would be occurred that Saul interwove the concordance elements and assimilated the discordance elements in paradigms, such as Suffering Messiah and different apocalyptic thoughts into one suffering Christ’s story (Phil 2:6-11).

The resurrected Christ emerged in front of Saul to question about why Saul persecuted Him (Act 9:4-5; 22:7-8), had triggered the contemplation of Saul. This was discordant with what Saul’s cognitive. To Saul, the incident of crucifixion of Jesus was originally an individual or “meaningless” occurrence[16] which was not intersect with his original Messianic belief. According to Rabbinic thought, Saul would quite accept the concept of “obedience” for which “martyrdoms” for Torah would be regarded as the supreme act of the extend. Thus, the death of Jesus Christ might be somehow concordance with concept of “obedience” (Rom 5:13-18, Phil 2:8).[17] Not only that, but also the “Story of Jesus Christ” mentioned in Scripture were in line with what Saul witnessed the life of Jesus, in terms of His personality of humility (Isa 53:2,4,7,11; Phil 2:7,8) and His life which was suffering (Isa 53:3-4,7-8,10) and obedience to death (Isa 53:9; Phil 2:8). The death of Messiah would be regarded as having the same meaning as the death of Jesus Christ which in turn would be the expression of obedience to God’s will.[18] But of course, the God’s will was revealed to Jesus in Scripture as well as the spiritual consciousness of Jesus Himself who in turn was the being of a New Torah according to the subsequent view of Paul.[19] Yet, Christ’s death was more than “martyrdom” of Jesus for God’s will. Further insight would hint from the word of “understanding” (בְּדַעְתּ֗וֹ “his knowledge” in Hebrew; τῇ συνέσει “in understanding” in LXX) (Isa. 53:11) (c.f: 1 Cor 1:19, Eph 3:4, Col 1:9, 2:2; 2 Ti 2:7) which was regarded as the true knowledge of mystery of God (Col 2:2), so “by His knowledge” or “in understanding”, many would be justified as righteous by this God’s servant. (Isa. 53:11) This could also be reflected in Phil 3:8-10 mentioning about knowledge of Christ and knowing Christ who was the basis for being justified as righteous rather than the Law (Phil 3:9).

Further inspiration to Paul would be the changes of Paul’s eschatological view that the resurrection had designated Jesus Christ, the Son of God, and from that moment the Kingdom of the Son was “actualized” (Rom 1:4). Actually, this combined the concepts of Messianic Kingdom and Danielic eschatology that both suggested the judgement and resurrection of dead would occur, except for expected one to be advent would be different. However, Jesus Christ fulfilled both in the way that He was the seed from David, and His resurrection might bring the imagination on the expected future advent in the form of supernatural being. Paul recognized that Jesus Christ is the one would be advent in future, so in Paul’s understanding, “the story of Jesus Christ” was emplotted into the plot of salvific act of “the Story of God and creation”. This is just as described by Ricoeur that discordant joined into a concordant plot.[20]

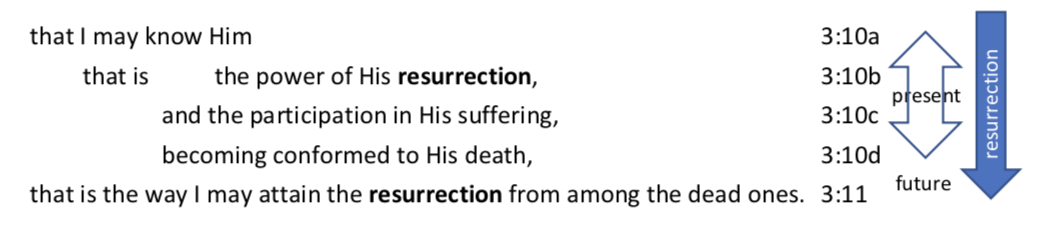

Also, Paul believed that the “Age to Come” which is eternally existent in the Heavens, had already appeared in initial stages in the resurrection of Christ. The resurrected body which is the body of the final “Age to Come”, was being formed already. He saw the beginning of the end in the resurrection of Christ, and we are already in resurrection of the powers of the “Age to Come”.[21] Also, the Parousia of Christ is the day of judgement for the world (Phil 1:6, 1:10, 2:16)[22] which would be the day of vindication for Paul and all believers (Phil 3:21). Here, twofold concept of the ‘ôlâm ha-bâ’ (“Age to Come”) would be similar to what J. Christiaan Beker’s suggested – bifocal character of resurrection: “Christ’-event” and “Parousia” (Phil 2:16, 4:1).[23] In this way, this may mean that the ‘ôlâm ha-bâ’ (“Age to Come”) has begun earlier from Christ’s resurrection rather than “Parousia”. This may also help explaining the inclusio pattern of “resurrection” (ἀναστάσεως in Phil 3:10b, ἐξανάστασιν in Phil 3:11) picturing the “resurrection” in the status of “already” but “not yet”.

All this demonstrated that there were concordance on the belief of the final resurrection but discordance in the time to experience of the “resurrection” in Paul’s renewal eschatological thought. The innovation could also be explained by the reasoning of “dialectic of innovation and sedimentation” under Ricoeur’s concept.

But what really meaningful to Saul and causing his conversion might be that the innocent and sinless Jesus would be crucified on the cross which were regarded as the most cruel and shameful way. In the Torah, “anyone who is hung on a pole is under God’s curse” (Deut 21:22-23), so crucifixion would be symbolized as that curse (further discussed in 3.2.2.1). Though the Messiah should have suffered may not have been entirely unexpected by him under the conceived concept of suffering Messiah. But for the situation that the Messiah have undergone the disgraceful and disgusting death of crucifixion and thereby incurred the curse of the Torah, this was a stumbling block (1 Cor 23) to Jewish. Only the experience of the Spirit alone enabled Saul to overcome, and transformed into “Paul the Christians” with Christian Faith (and also into “Paul the Apostle” who perceived new mission from God (Act 9:15, 22:14-15)) from “Saul the Pharisee”,[24] which was his original temporal identity (i.e. sinful “form” of Saul) by being buried with Christ. With the new temporal identity, Paul was able to be united with Christ and in the fellowship of Christ’s community, share one Spirit in one God and start an innovative narrative future. As explained by Ricoeur, if the plot deviates notably from its tradition (i.e. faith in Christ rather than Torah), then the innovative narrative (i.e. apostle life) with its intrinsic temporal identity has undergone an obvious change from its prefigurative tradition[25] (i.e. from Pharisee to Apostle). In Paul’s experience, this encountering would be impressive that shift the plot of his life story, so this was reflected from his decisive pursue in gaining Christ in any price (Phil 3:7-8).

Mimesis 3

As said before, “Paul the Apostle” received his mission (Act 9:15) and knew his destiny of suffering for the sake of Christ’s name (Acts 9:16). This would be drastic change in Paul’s life that the one used to murder against the disciples of Christ (Act 9:1), would become the disciples of Christ and be willing to suffer for taking risk of being murder for Christ’s name. The change of temporal identity which also empowered and admitted with the new ethical identity. He knew that “suffering for Christ” would be more than the meaning of martyrdom. From Paul’s perspective reflected from his epistles written afterwards, “suffering for Christ” would think of the intimacy with Christ by imitating Christ on suffering for others (2 Cor 1:6) and experiencing exhortation from Christ (2 Cor 1:5) and looking for future glorious (2 Cor 4:17, Phil 3:21).

Then, this letter was written by Paul in his new ethical identity, i.e. the apostle of Christ putting into practice (Mimesis 3). We could read this epistle in the way that Phil 3:5-11 was his own testimony in which Phil 3:5-6 (“Paul in Mimesis 3” to see the “Saul at Mimesis 1”) was Paul’s own review on the life of “Saul the Pharisee” from his new perspective of apostolic identity. It is believed that ἥγημαι (perfect middle) in Phil 3:7 might mark finished the period of discordance and concordance struggling about grasping “whatever things were gain to me” for the sake of Christ. This indicates the conversion into “Paul the Apostle” (“Paul in Mimesis 3” to see the “Paul at Mimesis 2”). The repeated ἡγοῦμαι (present middle) and ἐζημιώθην (aorist passive) in Phil 3:8 would indicate his continuous determination and the practices for “gaining Christ” , and for which he knew it would be obvious or had used to suffer loss once decided the way towards Christ. This was the start of Mimesis 3 of Paul’s later transformed story. We could also read in the way that “gaining Christ” and “be found in Christ” (Phil 3:8-9) would be Paul’s Christian ethical goal in present which directs his every ethical actions and decisions, but the ultimate goal would be being united in Christ through “knowing Christ” (Phil 3:10). His strong determination and the strength inside came from his “understanding” of mystery of God (c.f. Isa. 53:11, Cor 1:19, Eph 3:4, Col 1:9, 2:2; 2 Ti 2:7) that the soteriology and the future resurrection was from the Advent of Christ who would bring the glorious to the righteous by judgement and conformity of glorious body to His believers. This was the final vindication of present suffering. However, God’s power revelated through “resurrection of Christ” and Christ Himself not only opened the eyes of Saul to the mystery, but let Paul understand that “today determine the future”. No matter how suffering or even death, he would still count all privileges as loss or threat to intimacy with Christ and he won’t escape from what his role deserved to have. (c.f. Act 21:4-5) In Paul’s mind, there would be no fast track for being a believer or an imitator of Christ whenever suffering or death came in front of him. But doing as alike of Christ to be humiliate as His “form of a slave” which was a kind of subversion of the “patronage system” and obedient to death on cross shamefully which was in God’s will, Paul would surely do it if the same God’s will came to Paul. This might be the genuine meaning of Paul for “participating in His suffering” and “becoming conformed to His death” (Phil 3:10). All these was for the ultimate intimacy with Christ in the resurrection out of death (Phil 3:11).

Then, how the Paul’s transformed story affected the Philippians? Let’s us see ……

Footnotes

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 260-262. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 263. ↑

- W. D. Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1967), 263-265. ↑

- “Jews and Early Christians in Rome.” International Catacomb. http://www.catacombsociety.org/jews-and-early-christians/ (accessed April 1, 2020). ↑

- jewishencyclopedia.com. http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com (accessed April 1, 2020).It states that the crucifixion was originally put on slaves, and later also including freedmen of obscure station (“humiles”), then also on those committed serious crimes(such as piracy, highway robbery, assassination, forgery, false testimony, mutiny, high treason, rebellion) and solders that deserted to the enemy and slaves who denounced their master. ↑

- jewishencyclopedia.com. http://www.jewishencyclopedia.com (accessed April 1, 2020). ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 284. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 284. ↑

- Scott Yip, “Threefold Mimesis and Nesting of Stories”. Lecture Notes, (Hong Kong: Alliance Bible Seminary, 20 Jan 2020), 3. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 287-288. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 287.It states that “Messianic Kingdom” was Messianic expectation of the prophets in pre-exile and exile. The scion from House of David would arise and judge the nations and the righteous would be survived the sifting of judgement for entering His Kingdom. After several transformation, and the latest version would be that there would be resurrection of the dead at the advent of the Messiah in order that they too (i.e. the including the righteous) might be judged and be partakers of the Kingdom. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 287-288.It states that “Danielic eschatology” by which the Kingdom of God is made manifest not through the advent of a Messiah but through that of Son of Man who is a supernatural being. The inauguration of this kingdom, which is of a supernatural character, is signified by a general resurrection of the dead and their judgement. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 288, 296. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 296. ↑

- Yip, “Threefold Mimesis and Nesting of Stories”, 4. ↑

- Yip, “Threefold Mimesis and Nesting of Stories”, 5,6 ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 265. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 265. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 266. ↑

- Yip, “Threefold Mimesis and Nesting of Stories”, 5. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 297. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 296-297. ↑

- J. C. Becker, Paul the Apostle. The Triumph of God in Life and Thought. (Philadelphia: Fortress, 1980), 160. ↑

- Davies, Paul and Rabbinic Judaism – Some Rabbinic Elements in Pauline Theology, 228. ↑

- Yip, “Threefold Mimesis and Nesting of Stories”, 7. ↑

一個因讀提摩太後書感動落淚,而開始想研究二千年前的保羅的人……